Editor’s Note: Another outstanding entry from one of our regular and trusted contributors to The Prepper Journal. And, as always, if you have information for Preppers that you would like to share and possibly win a $300 Amazon Gift Card to purchase your own prepping supplies, enter today.

Whether it’s a survival garden or a small-space hobby plot and pots, the concept of producing “high value” crops periodically comes up. That term can be a little bit of a moving target, with a number of variables factoring in. Our growing season, desire for calories or balancing our stored staples with vitamin-rich foods, the amount of space we have in our plots or pots, the neediness of various plants, and other aspects all come into consideration. In an entirely different vein, we might highly value crops like teff (Williams’ lovegrass), yams, amaranth, and some of the perennials and wild edibles because they look less like a food item to most of the country, regardless of effort or yield-per-acre, or because they’re extremely drought or cold tolerant. However, we define value, we want to get the most for our efforts.

Most Common Factors in “Value”

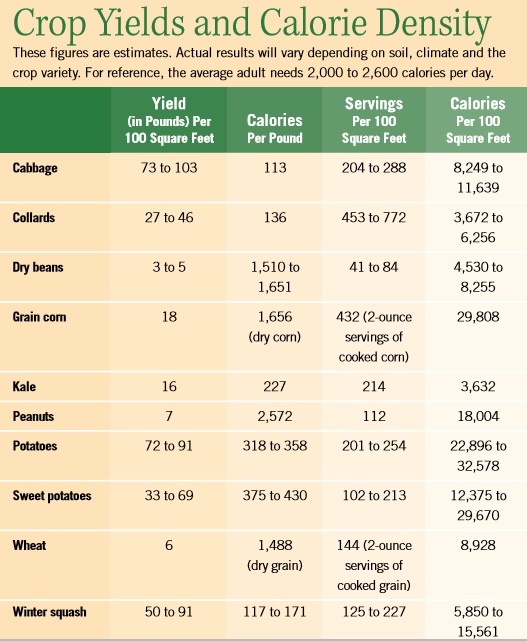

One of the primary factors in value for survival growers is the calorie density – per plant or per space or per week http://www.gardeningplaces.com/articles/charts/World-Staple-Crops-2009.png. Value is also seen as the total bulk for filling bellies by square foot or week, with calories only a secondary or tertiary concern. There’s also a current-cash-value or equivalent-to-cash-value that might come into play.

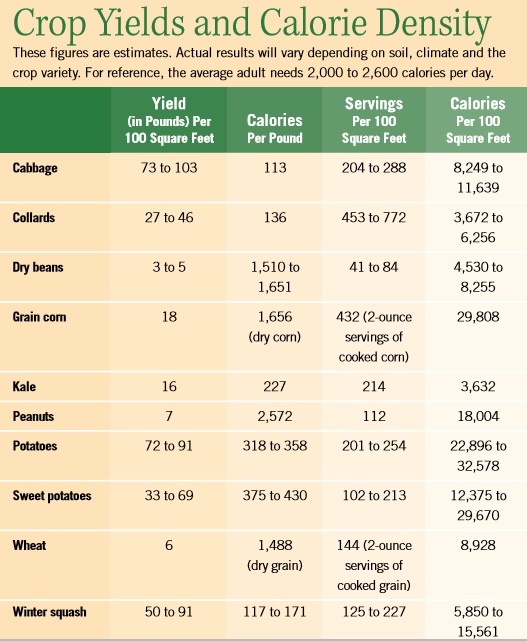

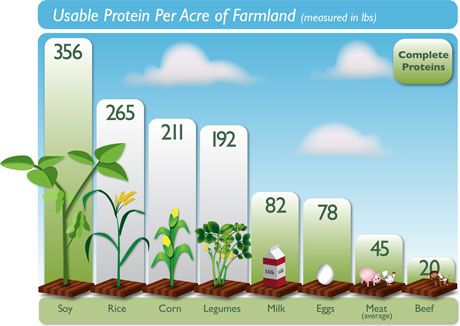

Staples like wheat, corn or potatoes all have significant calories per square foot or acre, and in the case of potatoes, per plant. Protein from crops versus livestock – and livestock’s feed needs – also merits consideration, large scale or backyard or condo/apartment dweller. Rabbits are quiet, cheap to feed, and need little space, but if we have the land, the protein and calorie boosts from eating closer to the bottom of the food chain may be more attractive.

Yellow squash and tomatoes can yield incredible amounts per plant. Cut-and-come-again salads can also yield enormous bulk over their cool seasons. However, they contribute little in the way of calories, and their value as a belly filler is limited by the fact that they really don’t keep you feeling full long the way high-fiber whole grains and proteins do.

Cash value might be split along the exact same lines – what can fill our bellies, for the price of seed or starts, or can eliminate buying the calorie staples in our diets. However, cash value is usually looking more at the price the crops can be purchased for or sold for instead of their nutrient or calorie yields.

Our calorie staples are some of the cheapest things in the supermarket. There’s a reason beans, rice and wheat are staples in low-budget diets, and why we see so much oatmeal, rice, and noodles in prepared storage foods.

If we’re augmenting calorie-dense foods that are stocked wide and deep in our pantries, our choices will be different than if we were truly trying to become self-sufficient and produce our staple beans and grains.

Space & Season Constraints

Our land space also affects just how reasonable an effort it would be to devote portions to those beans and grains, compared to storing the staples and growing vitamins and minerals to go along with them. The value we place on different crops changes the less we have, as well as where our soil is located.

Even a small suburban or urban gardener might be able to plant a 10 x 100’ stretch of wheat or barley that will yield 40-50 pounds off 6-8 pounds of seed.

With only windows and balconies or patios, a lot of the staple grains and even the dry beans for storage come off the table due to both the soil footprint they occupy and the amount of time they’ll need that soil. They’d do better to focus on storing the staples and growing either fast crops that can be quickly rotated and yield reasonable amounts even in a small space, or indeterminate tomatoes and summer squashes that offer the same regular, constant yields over a long period.

To get the same amount of staple crops as I do in my USDA Zone 7 with its seven frost-free months, a cold-climate grower needs to put more land into production than I do.

I can rotate even two long-growing crops into the same fields, pots and beds over the season, after and before additional cool-season crops. Somebody with 3-5 frost-free (or freeze-free) months has only the potential of greens, beets, radishes and turnips ahead of and behind their single main “warm” crop.

If that cold-climate grower doesn’t have the ability to start peppers and tomatoes indoors and has limited cold frames or greenhouse space, they might skip them entirely, or go for a much smaller, determinate variety and prune it to a single stalk very early in the season. They’d also potentially skip sweet potatoes and corn in favor of a Russian potato, barley or rye.

Because of our seasons, and the amount of space we have or would need to impact our food supply, the crops we value most – for their reliability and for their impact to calories, nutrients and “treats” – change.

Likewise, a small-space grower may eschew a long-growing plant like broccoli with one primary head and some smaller shoots or a ball cabbage in favor of the half-a-dozen or more Oriental cabbages they can produce in the same space and half to two-thirds the time.

Knowing the yields we can expect – tracked from our own properties and methods, not just the averages some put together http://www.ufseeds.com/Crop-Calculators.html — can help us significantly in deciding what crops hold the most value, and where we want to focus our storage versus our production.

Image: Neediness like cold sensitivity, high water & nutrient needs, and pest and disease inclined plants such as tomatoes, squash and sweet potatoes can affect how “valuable” a crop is compared to hardier veggies, grains or beans.

Other Factors – Health & Inputs

The effort we’re going to have to put into our crops can also change the value, and what we consider valuable for now and us, or for others and “after”.

Crops that are nutrient hungry, water intensive, and-or labor intensive might not be a great idea for our hand-cultivated garden in a busy life. The reverse is that those crops already or will have a higher trade or “treat” value than easy basics.

For some areas, potatoes and sweet potatoes are relatively easy to carry over through the winter, then start for “slips” that will be transferred to the garden or “calloused” into seed potatoes that are planted. For some areas, however, cellars are out of the question and it’s tougher to get those tubers and roots through the winter. Their value as an easy-handling staple or as a special treat vary by location.

Similarly, crops like tomatoes that need specific processes to collect their seeds and then tend to be potted inside and transplanted up, then out, could be considered high-labor. Carrots and cabbages that need a two-year cycle to produce seed would be considered needy in regards to the space they’re going to occupy so we can collect seeds to re-plant again.

Crops that are susceptible to pests and diseases, or that need regular weekly pruning would be considered either high labor or high input, especially if we have to stock the cures because we don’t have any natural production methods or plants that can prevent or cure the diseases. Tomatoes fall into that category, too, as do many of the most common North American tree fruits like plums, peaches and even some of the apple species.

In some definitions, the effort increases their value. However, on a survival level, they’d drop in value due to all the effort they require during a period we’re presumably already pretty tapped out.

Storage Considerations

Given our busy lives now and the labor we can expect in a disaster, we might also assign a high value to crops that go right from field to rack or bin or cellar instead of needing to be processed for storage or consumed quickly.

This can be seen in the difference in counter top/shed and fridge/cellar shelf lives of cut leaf lettuce, a melon or soft-skinned pattypan squash or zucchini, and cabbage or thick-skinned autumn squashes.

Softer, early-season, sweet-fleshed apples that will store for a few weeks or so straight off a tree have value in immediate foods and nice “to go” food value. They’ll sit somewhere – anywhere – a lot longer than peaches, berries or plums.

However, we will be processing them for drying, cider, or canning relatively soon, and typically during a very busy agricultural season that is racing our needs to replenish winter heating and cooking fuels, and the need to take advantage of summer and early autumn fishing, hunting and livestock harvesting.

With that kind of rush, we might place a great deal of value on one of the hard cider, baking or heirloom apples specifically meant to sit somewhere for months that we can harvest, inspect, crate, and stack in underground pits or our crawlspace or cellar, then come back to for additional processing after frosts, ice or snow have killed off some of their time competitors.

Image: Crops that need minimal processing for storage may gain in value.

It can also be seen in the different processing effort and time needed for the calorie-base beans and grains.

Starchy flour and popcorn corns take some work to husk. It’s a different type of labor than threshing wheat or oats. Hull-less and beardless grains, pseudo-grains like amaranth and quinoa that either rinse or only need winnowed, and beans or field peas that are readily separated from dry hulls all take far less work than heirloom North American grains.

Those in turn take a lot less labor and-or inputs like water for processing than some of the African grains like millet and teff, although other factors may make the more labor-intensive processing more attractive, since there’s a flood-resistant millet for pretty much every single soil and teff is one of the fastest grains, grows well even on played-out soils, and also makes good hay.

Teff is also one of the few grains that will handle a fast-pass graze that leaves 4-8” of stalk without any impact to its grain yield later. If we have livestock, especially birds, those hard round grains won’t be getting milled at all, or will only need cracked or to be sprouted, so the labor we’re going to put in post-harvest becomes partly or entirely nullified.

Image: The inclusion of small livestock in our survival garden can change the labor and input needs of crops, while creating a different set of needs and yields.

Factoring Value

There is no one be-all list of high-value crops, because we’re all different. There is only one constant, one-size-fits-all rule when it comes to producing food – get started.

Space, time, effort, season length, and plant neediness all affect which crops have the most value for us. Our growing style(s) impact how much work we can get done and how densely we can plant, as well as how many “outside” inputs our veggies and staples need.

The term “value” itself changes. There is value in being able to produce our base calorie staples, but there is also value in having those rainbow “diet food” veggies that are packed with nutrients. If we’re in “thrive” with a community around us, there is a great deal of value in producing sugar crops like stevia or beets, or tobacco, tea camellia, and caffeine-loaded yaupon.

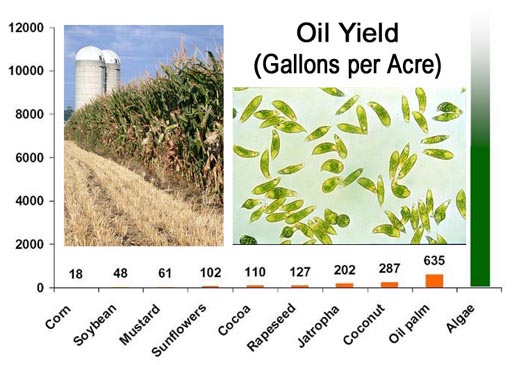

There is enormous value to self-sufficiency in learning to produce and stocking extra seed for oil crops such as peanuts or canola/rape http://www.thekitchn.com/whats-the-difference-between-canola-and-rapeseed-206047. Sunflowers for animal feed and for oil http://www.survivopedia.com/how-to-make-vegetable-oil/ are another that might have incredible value both for today’s self-sufficiency and after a disaster – even a “lower” major disaster on the scale of the Great Depression or Venezuela’s recent issues.

The presence of livestock may alleviate one need or input, lower some labor, and allow us to value a different crop, or focus on staples and veggies over oil crops.

There’s nothing wrong with going ahead and stocking seeds we don’t plan to use “unless”, but we can apply the factors in value there, too.

We might as well stock seeds for things that have one high value or another for those times when we can trade them out, take over curbside grass swatches and neighboring fields, and uproot city parks and stadiums. Knowing what a crop requires to go from seed to seed lets us stock wisely.

In the end, we each have to decide for ourselves which crops to focus on, from our storage totes on fire escapes and bottle towers in windows, to our triple-digit acreage in the Redoubt or South Texas. Knowing the factors that apply can help us make those decisions.