Editor’s Note: This post is another entry in the Prepper Writing Contest from frequent contributor R. Ann Parris. If you have information for Preppers that you would like to share and possibly win a $300 Amazon Gift Card to purchase your own prepping supplies, enter today!

We hear about how shotguns are the do-all when it comes to hunting and self-defense. What we don’t always hear is how to best choose one or that to make them a do-all, we need to know what to feed them. Some of what comes into play is because our game in the U.S. is highly regulated and with the exceptions of some private reserves and clubs and private lands, we end up competing for game. That competition isn’t likely to go down in the future. Some comes into play because we have drywall and kids and neighbors, and what we choose to protect them may not be best for hunting purposes.

Chokes and barrels

Two aspects of shotguns that matter most are our barrel lengths and the chokes in the barrels.

Barrel rule-of-thumb considerations

The longer the barrel, the longer shot is going to stay tight and the easier it is to “aim”. On the other hand, a 26-32” barrel is quite the cannon to be swinging around the doors and corners in our houses.

Big barrels also build up more momentum. That’s awesome for wingshooting and shotgun sports, most usually (skeet excepted), because we need to keep swinging for the shot and follow-through – just like in baseball. In a creak-in-the-night or repel-the-boarders situation, however, we typically want something we can readily change direction with. That means a shorter, lighter barrel.

The downside to a short, light barrel is that it is lighter. A lot of light shotguns are shoulder bangers. That can make them more difficult for some people to keep or get back on target for follow-up shots. Comfort is also important because practice takes more time than doing. We need to build the muscle memory, and that takes repetition. Age of the firearm, ammo loads, stock pads and style, shoulder pads, and the trick of weighting a stock with fishing shot can affect the felt recoil.

Weight in the field

Barrels make up a big percentage of the weight and length of a shotgun, but action type and purpose affect weight, too.

Semi-autos are heavier. The weight alone helps reduce felt recoil, but the action also helps absorb some of it. A sporting gun may very well have a weight in front of the magazine tube that increases momentum of the swing – that’s great for sports, potentially useful hunting geese and ducks, but it adds up to quite the package to haul around, especially when you carry a bag and water everywhere. In a defensive situation, we want to avoid things that lock us in to a particular direction. We take short steps and stay poised so that we can quickly change direction. Less weight becomes an asset, just like that shorter barrel on its own.

Break-action shotguns tend to be 3-5” shorter and significantly lighter than a pump or semi of the same barrel length, because their actions are so simplistic. They lack the chamber and feeding mechanisms of the others. This contributes to their being about the lightest shotguns to carry, and it’s why some call over-under guns “whippy”. That’s great in some field situations, although I tend to want to max out my 3-5 legal rounds, not be reduced to two, and at home I for-sure don’t want to limit shells.

Clearing up chokes

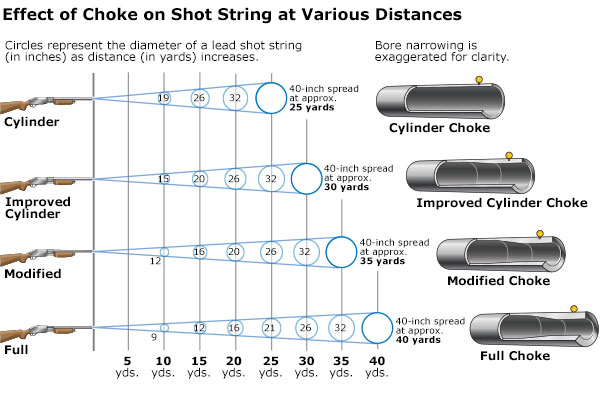

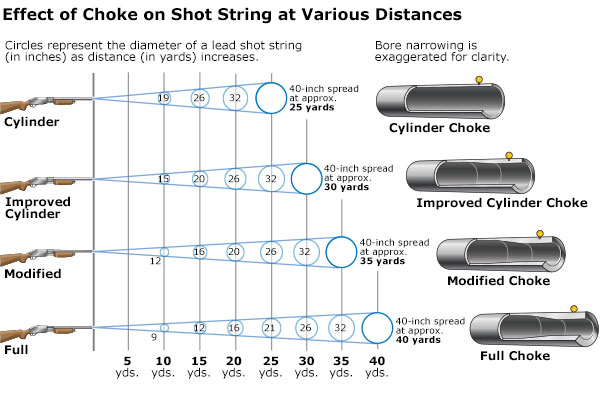

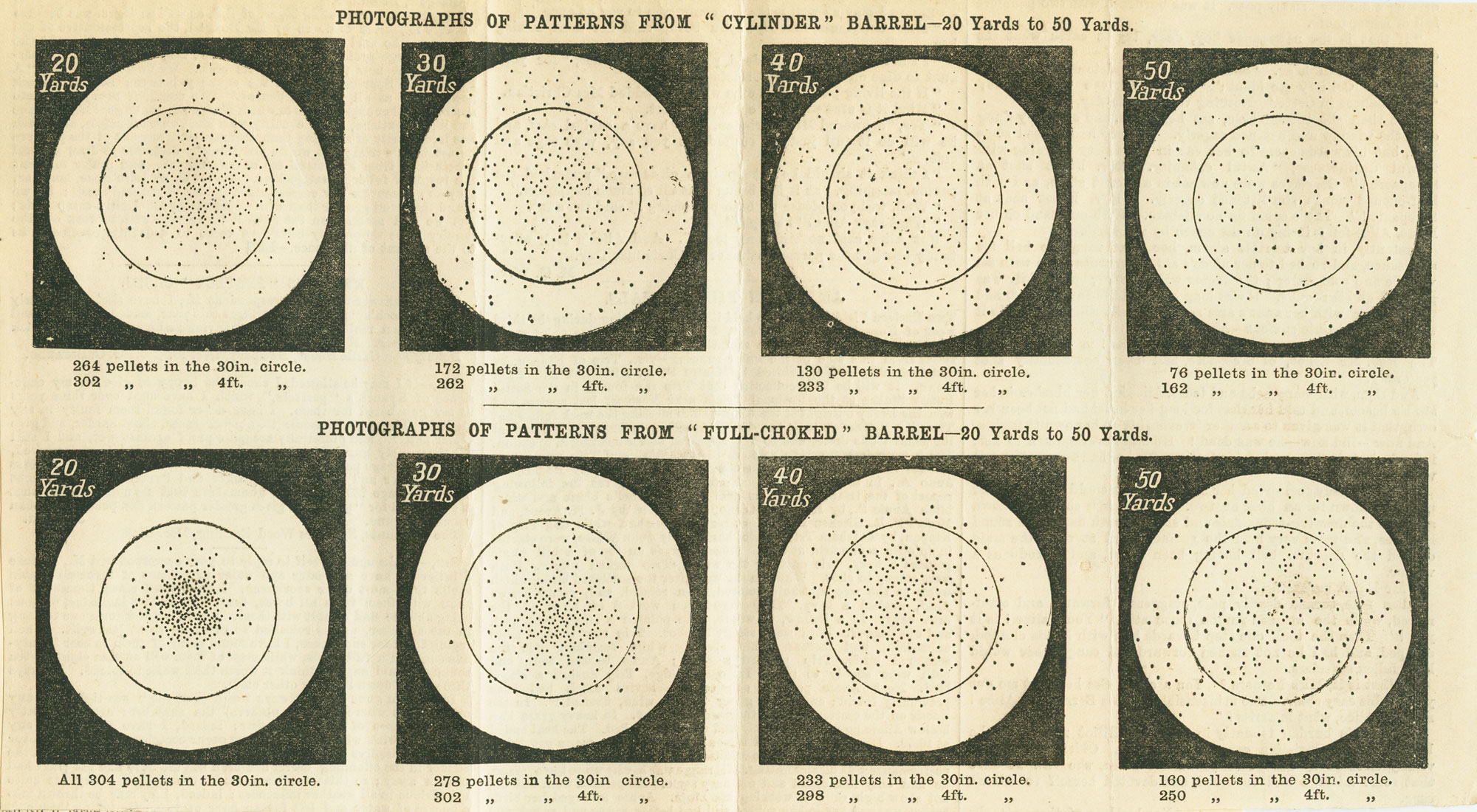

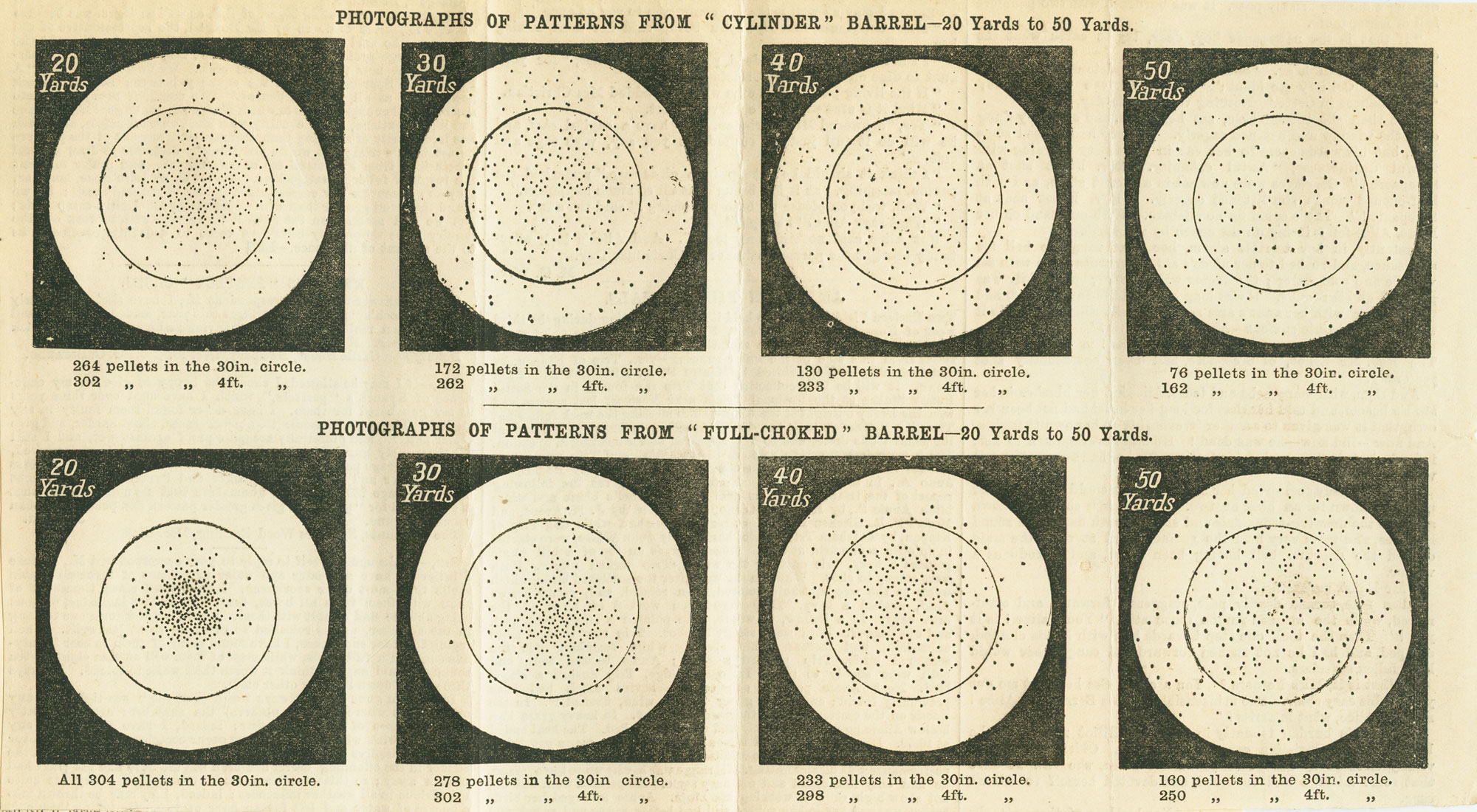

As much or even more than barrel length, chokes influence how tight our pattern of shot stays. The goal I’ve typically seen is for your shot to be spread to about 20-40” at your target distance, but there’s play there.

I’ve been a shotgunner for more than a decade and a half. I still don’t know all the very many chokes manufacturers have come out with. But I do have a quickie tip for shotgunners that can help keep track of the words rattling off enthusiasts’ tongues.

First make an okay sign with your fingers. Then close your hand into a fist.

- Okay = O = Open – Open cylinder/Open bore, CYLINDER bore, the widest choke

- Fist = F = Fully closed = Full – FULL chokes, the tightest choke

- Modified and all the variants are in the middle. (Conveniently, M.)

Why does the shotgun choke matter?

If I have a tight choke and am shooting high speed, small pellets, there may be so much shot that a game animal ends up turned into burger. Likewise, if I have a loose choke and take a 40-60 yard shot, especially with BB or low-number shotshells I may have 15” and 30” gaps in my shot pattern. That open pattern may let something fly or zing right through unscathed, but even worse, I may injure an animal lightly enough for it to get away now, but it will later die. That’s not responsible hunting.

On the home-defense side of shotguns, a tight choke keeps more lead hitting a bad guy instead of my walls, pets, and loved ones. But the reverse of that is that a full or modified choke can create a longer “string” of pellets and if I miss, the leading pellets can chew through drywall and open a keyhole for trailing pellets to pass through, endangering my neighbors and loved ones again. Pellet type and size and slug type and size can mitigate some of the risks, but there’s a point where if a shotgun is our go-to, we just accept whichever risk we’re more comfortable with.

Newbies now go “oh my [favorite deity or Mother Nature], now we’ve got barrel lengths and chokes and she mentioned numbers with the shotshells”.

Yes, it’s that bad, but, no, it doesn’t have to be that bad. There are guides that tell you what to use at what range, and we’ll get much deeper into shot in the future. The important thing to remember is not to put buckshot or slugs through a barrel with a choke screwed into it, or you’re going to have an Elmer Fudd moment. I hunted on an open choke 12-gauge and a full choke 20ga. for a very long time before I knew I was supposed to care – you just have to know the shotgun and patterns, and I have some tips for that later.

Pick a shotgun that’s versatile and upgradable

There are shotguns like the venerable Mossberg 500 and Remington 870 and 1100 that have been around forever. Because of that, they tend to be inexpensive and they have tons and tons of off-the-shelf, plug-and-play customizations available, so the gun can grow with us and our budgets if we’re inclined.

That means we can very easily lay on a shotgun with spare parts readily affordable and available, and one where we can get a short 18.5-22” creak in the night barrel and a 26-30” field and marsh barrel.

Feeding a shotgun – The shot size and shell weight relationship

Shot leaves the barrel and flies as a cigar or teardrop; it doesn’t leave the barrel all at once in a flat pattern. Picture the shot pattern forming a connect-the-dots spider web just this once anyway.

The more shot, the tighter the net of that web. The more strands the insects hit in a web, the better chance the bug gets tangled, and the better the chance the spider eats today. Little spiders hunt gnats and big spiders want grasshoppers and moths. A really little spider might lose a big fly because its web isn’t strong enough or it needs to get there fast (AKA: be closer to its target).

When we connect the dots in our shot pattern to make a web, we get the same relationships. Then we add in velocity (strength of our web strands) and – if inclined – further tailor our web size and gaps with our chokes.

Like I said, chokes matter, but I hunted and still hunt on a 1980s 870 with a cylinder bore. I am not Carly Hathcock, long lost genetic throwback to Carlos. It can be done. It was done all the time by our ancestors and grandparents. I do have to know that I’m limited in range with my shotgun, even with high-velocity rounds, which is where practice comes in. I need to know what size web I’m throwing to effectively and responsibly take my dinner.

Practice like you play

AKA, “The more you sweat in peace, the less you bleed in war.” In this case, the more we truly know about our shotguns and shells, the more we make our targets bleed.

A cardboard box makes a handy target, especially if you can lay on an open area and a bunch of boxes and cans about the same sizes as your targets. There are a wealth of life-sized paper targets that can be purchased, or we can get away with stick figures and ovals and triangles to draw our own with dollar-store markers and the freebie newspapers in front of grocery stores. Do a bunch so you can set up bunches at once and don’t have to run patch (dollar store tape) after every shot. Especially at the greater distances, that’s no fun.

Take a notebook! And a pencil!

Aim in front of the nose for flying birds, leading or upper chest for small mammals (generally), and run varying sizes of shot through your shotgun. Back off once you have a decent baseline. Measure as you go (pace it and compare that to a yard later).

Take at least five or six shots from that distance, minimum – ten or twelve is better. If you have any one shot that entirely misses the target or only lands 1-2 pellets somewhere in a wing or non-vital area, you need to scoot in again.

When you get to the point when you’re only putting 3-5 pellets in your non-moving targets, that’s your absolute max range with that choke and that ammo.

Write it down.

Write down the shotgun, choke, distance, and the ammo (manufacturer and ammo name, like “Super X”, the dram or dram equivalent in inches, the powder load or velocity, and the shot size and weight of shot – 1 oz. of #5 or 1-1/8 of #7, whatever it is).

Take the notebook when you graduate to clay pigeons for moving practice, too, because “sport” loads tend to be a lower-velocity round than game loads, and that can affect where in space the bulk of the shot is “landing”. I have some super speedy ammo that lets me use it at ranges my slower ammo won’t.

The important information on the box

I’m not talking about the dram/dram equivalence or the gauge. Match that to what your barrel says and let that go, especially for new shooters.

Velocity matters. It’s marked in fps (feet per second) but usually a box will also tell you it’s for sports or have a little flying disk on the flap, or it will have some kind of critter shown on that flap and say “game”. Some say “waterfowl” specifically. Until you’re super happy and digging in even deeper, that’s sufficient and you don’t really need the math or background there.

What is important – for hunting, especially – is the shot size (#8 or BBB or 00) and the amount of shot inside the shell (that’s in ounces, usually 7/8, 1, or 1-1/8).

Big shot/smaller numbered shot weighs more. Fewer balls will be in a shell. Because it’s big and heavy, it hits harder. You use it on larger game and at greater distances to avoid wrecking meat and wasting animals.

Each ball in the higher-numbered small shot weighs less. I get more balls in each shell, but their lower individual mass means lessened ranges and decreased penetration. That makes them perfect for small game and small birds, but insufficient for things like jackrabbit and goose. It also shortens the distance they can be used for responsible kills.

When it comes to home-defense rounds, the distances matter, but so does the family and internal construction. Most steel or alloy, Hevi-Shot or slug will go through 1-2 layers of drywall like butter, as will buckshot, and some will go through 4 layers with 12’ between them. Some of those handy rounds with peel-away lead will go through cinder blocks. Great for a thug in a heavy coat. Not great for whoever is on the other side of the bad guy, or a wall or window.

Picking the right shot size

Shot size tells you how big the little balls inside are. Just like I wouldn’t shoot a bunny in my front yard with a .308 or 5.56, I don’t need to hit a dove with a B or #2.

Bad guys deserve a faceful of whatever they get. If I pick birdshot to limit how much goes through drywall, I might want to aim for that face and throat instead of center mass, whereas inside-house ranges mean I can usually hit anywhere with a slug, and even in body armor he’ll jerk a little. It’s hard for him to aim at me if he’s getting punched in the chest.

There are shells made for home-defense that take drywall into account, and there are loads that just make bad guys puddles. You have to research each while weighing your priorities.

There are some super helpful guides that can provide you with general rules for game type. These are just a few:

- http://www.shotgunworld.com/amm.html (Side down for charts, to include a game guide near the bottom)

- http://www.ableammo.com/catalog/hunting_game_guides.php (expansive game-shot chart)

- http://www.chuckhawks.com/shot_info.htm (quickie shot-sport and shot-game list)

- http://guide.sportsmansguide.com/game-guides/ (detailed game-to-shot and choke chart)

- http://www.gunnersden.com/index.htm.shotgun-game-guide.html (game guide charts, but also steel-lead comparisons and slug comparisons)

Shot weight and shotgun gauge

The number of little balls inside the shell can be figured out from the weight listed on the box, and here: https://support.remington.com/General_Information/Guide_to_Shotguns_and_Shotshell_Ammunition. I think shot size is far more important, but the weight of pellets (in ounces) can affect the velocity as well as the spider web our shot forms.

I personally don’t find any success differences between 1 and 1-1/8. What I do see a difference in, is between the 7/8 of bird shot in a 20-gauge and the 1-1/8 ounces of shot I can get in a 12-gauge. I have half again the weight, which means I have a pretty significant increase in the number of balls for shot between #9 and #5.

That increase gives me a better chance of a couple of those balls hitting and one of them hitting the right spot to drop something right there where I hit it, off a branch or folding up its wings and falling from the sky.

Shotgunning suggestions

Because they can be so versatile by getting a workhorse shotgun platform, two barrels with screw-in chokes, and selecting shells to fit our uses, shotguns really can handle a lot of jobs for us. We do need to do more than take it out of the box and hang a bunch of stuff from it (without hanging a sling a frightening amount of time).

For an adult shooter, a 12-gauge will be more versatile going into the future and there are a lot more specialty shells available for 12’s than for 20’s in home defense and hunting. Yes, I hunt on a 20, but a 20 limits my range and game due to the amount of shot the shells hold, especially wingshooting and hunting on running rabbits. There’s some difference in recoil, but not a ton. Get a 12-ga. instead.

The most important thing to remember when shotgunning is that 20-gauge shotshells are yellow.

They are all now yellow and have been for years. There are now no yellow 12-ga. rounds. That’s because a 20-ga. shell will cycle in a 12-ga. shotgun, will get pushed forward and lodge in the bore, and will leave just enough room for a 12-ga. round to cycle in behind it when we rack the slide or bolt because nothing went bang. Then the 12-ga. round will go off – with nowhere to go. It will blow out the action of our shotguns, routinely hurt somebody, and regularly will get lucky and hit the primer of the 20-ga. in front of it. So now we have a shotgun spitting hate and discontent from both ends of the barrel.

That is a bad day.

Keep an eye out for yellow shells and just don’t have them anywhere near a 12-ga. shotgun. For sure do not keep both 20- and 12-ga. shells in your midnight-noise bag/slide or hunting vest, because dark, panicky and exciting moments are a bad time to trust we’ll recognize a 20- and a 12-gauge round from each other.