I can’t imagine housewives today saving used cooking grease in a can to take to the butcher in exchange for a few cents and extra meat rations, yet that’s what millions did during World War II.

Reading through a 1944 “Good Housekeeping” magazine the other night, I began to comprehend the extent of wartime frugality I’d heard about from old-timers through the years.

The movie “It’s a Wonderful Life” reminds us about scrap metal, rubber and paper drives, but I never really considered how rationing affected people daily.

I should have learned from my mother, who was a youngster at the tail end of the Great Depression and war. I attributed her thriftiness to a poor childhood. The seventh of nine children, my mother’s household (with only one wage-earner) grew to 16 with the addition of an aunt and five cousins after my grandmother’s death.

My mother still cuts buttons and zippers from old clothes to reuse. She shamelessly patches jeans, darns socks and makes quilts of worn-out clothes and linens. She once remade a pink flowered housecoat into a jumper for me as a child. Nothing was wasted.

Although we were middle-income, my parent’s conservation extended to every aspect of our household. I can still hear them telling us kids not to waste water in the yard with the garden hose. (My sister and I assumed water was free and infinite.)

Something happened to change people’s behavior since that humble time. Was it the abundance of cheap imports, the convenience of big-box shopping, or maybe government handouts of everything from surplus cheese to digital TV converter rebates?

Whatever the cause, I haven’t seen socks darned since the 60’s.

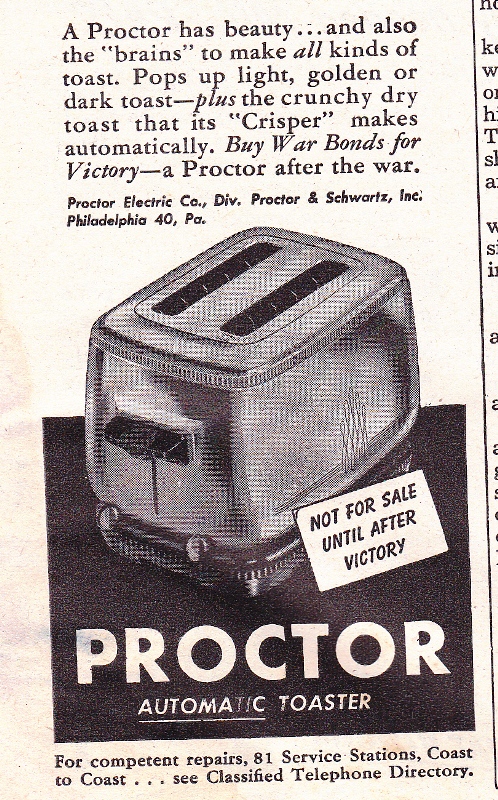

The ads in this 70-year-old magazine are particularly revealing of the scarcity of many products.

Unavailable until Victory

For example, the Servel Company (in a full-page ad, no less) touted the noiseless, trouble-free benefits of its latest gas refrigerators while the company was “100 percent on war work.” Servel wasn’t even currently selling appliances to the public, only for the Army and Navy, but says, “After the war, we expect to make more gas refrigerators than ever – and even more attractive ones!”

Servel and many other appliance makers advised consumers to buy war bonds, save money and plan ahead to purchase a gas refrigerator or air-conditioning system after victory. “If you plan to modernize your home after the war, there’s nothing unpatriotic in thinking about it now.”

Throughout the magazine, food ads and recipes explain how to stretch meals and use substitutes for just about everything. “To make the most of your meat ration – buy the best!” says Armour and Company. Swift’s says people can still occasionally enjoy two servings of meat in one day if they save their bacon drippings to use instead of butter and turn rendered fat in to the government to earn meat points.

Saving fat for war materials

In one article, readers are reminded to save “every precious drop of kitchen fat.” After fats became scorched, too dark or too strong to reuse for cooking, they were reclaimed to make explosives, medical supplies, recoil machinery for big guns and other vital war materials. Housewives poured melted fats into metal cans and brought them to meat dealers. They were paid 4 cents per pound, plus two ration points, for a pound of fat.

“A tablespoon a day will make a pound a month,” the article states. “Make up your mind to save at least that much every day. It’s one of the most patriotic and helpful things you can do to shorten this war. You can save American lives right in your own kitchen!”

Del Monte Foods says, “Whether your stamps dictate much or little – Del Monte flavor will do a lot for most any dish in any wartime meal.”

In another ad, radio personality Kate Smith says many of her fans write how they are “using less than their rations because they want to share and play square.” Many wrote to her of their Victory Gardens, canning produce and food-saving ideas. They never “whine or complain” about rationing, Smith says.

Apparently, sharing and playing square was a common wartime expression. A logo “Food Fights for Freedom” is repeated several times in the magazine. Kraft says food waste is sabotage.

An advertisement by Sanforized Company alleges it is practically criminal to throw out clothing that could be made into dust cloths. “Throwing away clothes today is a form of sabotage.”

Other articles explain how to brighten a room by making curtains of old white bed sheets, wash a lampshade instead of throwing it out and to make kitchen cabinets of salvaged lumber.

Many items scarce

The American Gas Association advised of a post-war dream where housewives will “live like a princess in a house that runs like magic” with all gas appliances. So few sewing machines were available to buy that Singer rented them to customers by the month or hour at sewing centers. What a nuisance that must have been.

Paper, too, was in short supply. Hearst Magazines apologized for the limited number of issue copies. “Restrictions on the use of paper, made necessary by the war effort, make it impossible for the publishers to print enough copies of GOOD HO– USEKEEPING to meet the monthly demand. Will you be a good soldier, too, and, when you have finished with your own copy, pass it along? Such sharing will help everybody.”

Ironically, I found this magazine used as wall insulation in an old farmhouse, perhaps after it had been shared throughout the countryside.

Conservation today

Much has changed since 1944, hasn’t it? I admire the women who wrote to singer Kate Smith to relate how they actually used less rations than allotted. What a challenge that would be for many today who grew up in the illusion of abundance.

With reminders of past hardships and uncertain times ahead, it may be wise to adopt a skill of frugality and learn to preserve what we have because it may not be plentiful later. Could we live like it is 1944 again? I like to think so.

Please check back for upcoming articles about mending clothing, assembling a handy sewing kit and remaking discarded articles into useful household items. Maybe we’ll see some darned socks and patched pants again.

Frequent contributor, Linda Holliday lives in the Missouri Ozarks where she and her husband formed Well WaterBoy Products, a company devoted to helping people live more self-sufficiently off grid, and invented the WaterBuck Pump. A former newspaper editor and reporter, Holliday blogs for Mother Earth News, sharing her skills in modern homesteading, organic gardening and human-powered devices.